The future is arriving—a few tons at a time—at Suncor Energy Inc.’s North Steepbank oil sands mine in Alberta, Canada. Human-operated excavators scrape away the top layers of soil to get to the hydrocarbon-rich tar sand beneath in much the same way they always have. But now they’re dumping that dirt into driverless trucks that use GPS systems and lasers to find their way through the massive mine.

The trucks, part of a multiyear test, are just one way that Suncor and other oil sands producers are trying to bring down the cost of what traditionally has been one of the most expensive ways to extract crude.

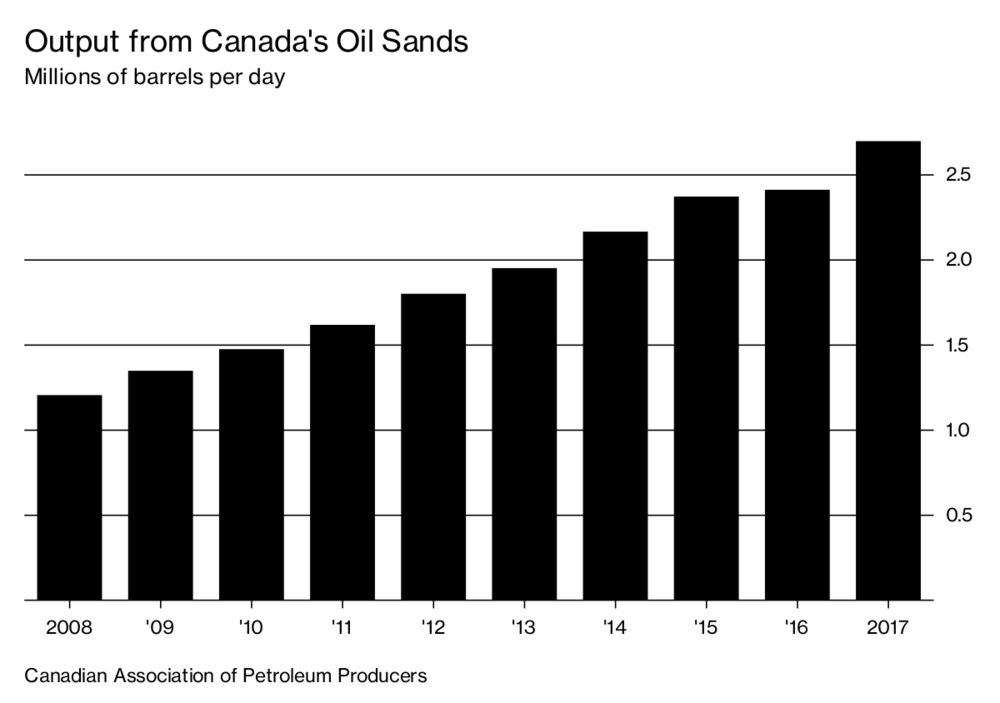

Canada’s tar sands, which contain the planet’s third-largest oil reserves, were a prized possession for global energy companies when crude was trading above $100 a barrel. But since prices fell to $50 in 2015, where they have lingered, Royal Dutch Shell, ConocoPhillips, and Marathon Oil have unloaded their holdings amid concerns that these capital-intensive projects would struggle to turn a profit.

The Canadian companies that have snapped up those assets are chipping away at those fears, using automation and other new technologies to drive down operating expenses. “They are making great progress and showing that they can be healthy and make money at $50 oil,” says Justin Bouchard, an analyst at Desjardins Securities in Calgary.

In recent earnings announcements, Suncor and rival Cenovus Energy Inc. said they can now sustain production with oil at $40 a barrel without jeopardizing the dividend they pay shareholders. While that’s not yet near the economics of shale producers in Texas’ Permian Basin, where the break-even price can be as low as $25, additional advances on the horizon could make oil sands production even more efficient, Bouchard says. For instance, companies are experimenting with injecting solvents such as propane into reservoirs to recover more of the sticky crude. They’re also running tests that use radio waves, instead of steam, to heat the sand so oil can flow to the surface.

In addition to lowering production costs, the innovations may help cut carbon-dioxide emissions, giving the industry an image boost it badly needs. The reputation of tar sands as the world’s dirtiest source of crude has been at the root of opposition to proposed pipelines connecting mines in Alberta to refineries in the U.S. capable of processing the heavy Canadian crude. Former President Barack Obama blocked the construction of a segment of TransCanada Corp.’s Keystone XL pipeline, but moves by his successor could revive the project.

Oil sands producers have at least one advantage over their rivals in the Permian: longevity. Many of the tar sands deposits hold 50 years of oil, while shale wells tend to exhaust themselves within months. “There is always predictable feedstock to deliver, and that allows us to use continuous improvement processes and leverage technology to become more efficient,” says Steve Laut, president of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., which is pouring C$1.6 billion ($1.3 billion) into research to reduce the amount of wastewater generated by operations.

Despite recent advances, oil sands operators are still among the highest-cost producers in the world. A continued decline in crude prices could severely wound the industry by deterring investment. Large deposits, such as Imperial Oil Ltd.’s Kearl, can cost more than $10 billion to develop over a decade or more. Laszlo Varro, chief economist at the International Energy Agency, sees the industry “focusing on smaller-scale projects that they can execute in a couple of years and manage the costs effectively.”

%20(1).png)