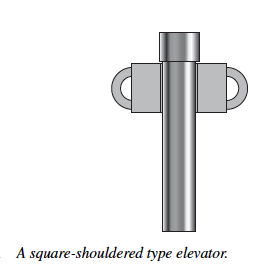

A wide variety of the elevator and spider assemblies are available to run casing. Some elevators are what is called square shouldered (see Figure -1), they have no slip elements. Instead, they have an internal diameter that will fit around the casing body but is too small for a coupling to pass through; they have hinge openings. The spider may be similar to the elevator and hinged or large enough for the coupling to pass through with some type of slip assembly built in, or there may be just a simple set of manual slips.

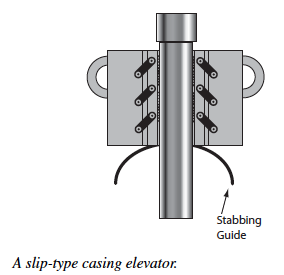

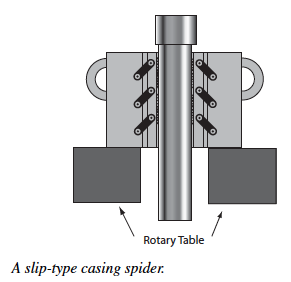

Elevators and spiders increase in sophistication from there. We assume that anyone who runs casing knows to select an elevator and spider combination of sufficient strength to suspend the casing safely. There is one important point to make in this regard though. The elevator and spiders (see Figure-2 and Figure–3) normally used to run heavy casing strings are rated at 500 tons (1 million lbf) or even 1000 tons (2 million lbf) and have an internal slip assembly that is either manually activated with an external lever or is air or hydraulically actuated.

Figure -1

Figure -2

Figure -3

These are very good tools for running heavy strings of casing. The problem is that even a heavy string of casing is not “heavy” when it starts in the hole. The efficiency and ease with which the manual lever operates the slips is such that it is possible for someone on the rig floor to easily open the slips even with several hundred feet or so of casing suspended in the spider. A similar problem can occur when the pipe is in the elevator and an obstruction is hit, causing the load on the elevator to be momentarily released so that the slips jump open. The result in either case is a portion of a casing string dropping into the hole and going to the bottom. For this reason, it often is preferred to start a long string of casing in the hole with lower-rated tools, then switch over to the 500 ton tools when the casing is at the bottom of the surface casing or some other point where the running process can be paused to switch the elevator and spider. The possibility of such an event may sound remote, but a number of these instances inhabit many companies’ annals of bad events. In one case, a casing crew member slipped and fell against the release lever on a spider and dropped 400 ft of 13⅜ in. casing to the bottom of a 5000 ft well. In another case, the crew was not filling the 7⅝ in. casing properly, and as the driller lowered the casing, it was buoyed enough that it did not descend at the same rate as the elevator; the elevator slips opened. No one realized the elevator slips were open until the driller stopped the elevator above the spider and the casing kept on going right through the spider before anyone had time to react. Approximately 1100 ft of 7⅝ in. casing fell 12,000 ft before it stopped. One other point about casing tools is that a spare elevator-spider combination should be on the rig, in case there is a problem with the primary tools. There will not be time to order a replacement if one fails in the process of running casing.

%20(1).png)