Casing is manufactured in several different grades. Grade is a term for classifying casing by strength and metallurgical properties. Some of the grades are standardized and manufacture is licensed by the API; others are specific to the particular manufacturer.

API Grades

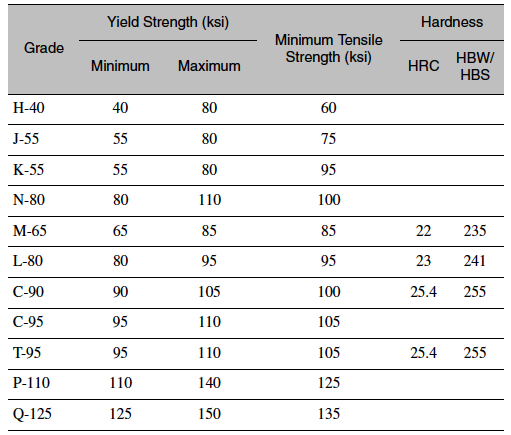

The API grades of casing are manufactured under a license granted by the API. These grades must meet the specifications listed in API Spec 5CT (2004) or ISO11960. These grades have yield strengths ranging from 40,000 lbf/in.2 to 125,000 lbf/in.2. These grades are listed in Table below.

The letter designations are essentially arbitrary, although there may be some historical connotation. The numbers following the letters are the minimum yield strengths of the metal in 103 lbf/in.2. The minimum yield strength is the point at which the metal goes from elastic behavior to plastic behavior. And it is specified as a “minimum,” meaning that all joints designated as that particular grade should meet that minimum strength requirement, although it is allowed to be higher. Typically, we use the minimum yield strength as the design limit in most casing design. The yield strength also may be higher than the minimum, and a maximum value also is listed in the table. The reason for the maximum value is to assure that the casing sold in one particular grade category does not have tensile and hardness properties that may be undesirable in a particular application. Some years back, it was common practice to downgrade pipe that did not meet the minimum specifications for which it was manufactured. In other words, if a batch of casing did not meet the minimum specifications for the grade it was intended, it could be downgraded and sold as the next lower grade. There also were cases where one grade was sold as the next lower grade to move it out of inventory. Some of the consequences of this practice were disastrous. One typical example was the use of N-80 casing for tieback strings and production strings in high-pressure gas wells in the Gulf Coast area of the United States. Many of these wells drilled in the 1960s used lignosulfonate drilling fluids and packer fluids, which over time degraded to form hydrogen sulfide (H2S). As it turned out, some wells that were thought to have N-80 grade casing, actually had P-110, and there were a number a serious casing failures due to hydrogen embrittlement. Many of these “N-80” casing strings had P-110 grade couplings on them, and in some wells almost every coupling in the entire string cracked and leaked.

You will also notice in the chart that some different grades have the same minimum yield strength. Again, this is a case where the metallurgy is different. For instance both N-80 and L-80 have a minimum yield strength of 80,000 lbf/in.2, but their other properties are different. L-80 has a maximum Rockwell hardness value of 22 but N-80 does not. N-80 actually might be a down-rated P-110 but L-80 cannot be. The grades with the letter designation L and C have maximum hardness limitations and are for specific applications where H2S is present. Those hardness limits are also shown in the table.

API Casing Grades, Tensile Strength and Hardness Specifications (API Spec 5CT, 2001)

The ultimate strength value listed is the minimum strength of the casing at failure. In other words, it should not fail prior to that point. This is based on test samples and does not account for things like variations in wall thickness, pitting, and so forth. It is not really possible to predict actual failure strength, because there are too many variables, but this value essentially means that the metal should fail at some value higher than the minimum. Also shown in the table are values for minimum elongation. This is specified as the minimum percent a flat sample will stretch before ultimate failure. When you consider that K55, for instance, yields at an elongation of 0.18%, then you can imagine that nearly 20% elongation is considerable. But one should not be misled into thinking that, if we design casing with the yield strength as a design limit, there is necessarily a considerable additional “strength” remaining before the casing actually fails. Once the material is loaded beyond the elastic limit (yield) the incremental stress required to stretch it to failure can often be quite small.

Non-API Grades

Non-API grades of casing are not licensed by the API and consequently do not necessarily adhere to API or ISO specifications. This is not to imply that they are inferior, in fact, the opposite is true in many cases. Most non-API grades are for specialized applications to meet requirements not covered in the API or ISO specifications. Examples are hightemperature and or high-corrosive environments and high-collapse and tensile-strength requirements. In these cases, one must rely on the specifications, quality control, and reputation of the manufacturer. For extremely critical wells, many operators elect to do a number of qualification tests and inspections on the specific casing that will be used in a particular application. For instance, one operating company has invested a very large amount of money and research into qualifying connections for use in high-pressure wells (Valigura and Cernocky 2005).

It should also be mentioned that a number of manufacturers make casing that supposedly meets API/ISO specifications but are not licensed to do so. Typically, this casing is sold below the market price for API/ISO casing. While some of this pipe has been found to be acceptable, much of it is not. This was a particular problem in the late 1970s, when the demand for casing far exceeded the supply, and similar situations reoccur from time to time. It is a case of “buyer beware.”

%20(1).png)